The use of "organic" in food marketing is highly unregulated outside the US and the word "sustainability" is un-standardized and means both wild and farm raised. The USDA, a government agency that regulates agriculture in the US with the intent of protecting consumers, has guidelines about what can be labelled as organic but is so understaffed that labeling abuses are all too frequent and unenforced. And, the harvest standards are different across the many segments of the food industry, from meat production to fresh produce to fruit to fish and seafood.

The current USDA definition of "organic" is:

"Organic is a labeling term that indicates that the food or other agricultural product has been produced through approved methods that integrate cultural, biological, and mechanical practices that foster cycling of resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity. Synthetic fertilizers, sewage sludge, irradiation, and genetic engineering may not be used."

"Organic" is not the same as "natural", even though by a plant or animal's chemical structure it is. And, it certainly does not mean that fertilizers aren't being used to cultivate the food source. A farmer can feed GMO soybeans to his chickens and produce organic fertilizer from the dried chicken droppings; which is then tilled into the soil to produce more food. Can it really still be considered organic? Of course, because we're only looking at the end product and not the whole process of how that product gets to the market.

The myth of sustainability is that if we (as farmers/gatherers/food producers) use herd management best practices, this food source can be harvested indefinitely. If you think that eating buffalo meat is healthier and better for you because it's a leaner meat than beef, and you eat it because it isn't raised on a farm, think again. All buffalo meat in the US is farm-raised and the herd is roughly 500,000. All wild, free-range buffaloes in the US exist only in environmental and government preserves--and hunting these is a crime.

Our greed and growing appetite for consumption fuels these myths.

Think you're supporting a small food co-op, family farm, or responsible food producer? Take a look at this infographic and see who owns these popular organic food products.

The natural evolution of marketing is like this: a thought, a concept, a plan, execution, implementation, and consultation after the fact. The problem that most companies suffer from is they go from thought to execution without any concept or plan. Then they rely on consultants to tell them what they already know. Outside validation is what's important. If two people agree, that's collaboration. If three people agree, it must be a trend. Or is it?

Google's Blacklist, Pt 1

Email deliverability is one of the many struggles with legit businesses offering products or services through email. ContentTech just had their online marketing summit a few weeks ago and a lot of the follow-up B2B emails from the participating vendors have ended up in the Gmail spam folder, even though it was clearly stated within the online conference that you were going to be opted into partner messages if you responded to offers or downloaded sales content.

Examples of Google's spam filter messages:

Examples of Google's spam filter messages:

- It's similar to messages that were detected by our spam filters.

- Many people marked similar messages as spam.

- It contains content that's typically used in spam messages.

In the case of T-Mobile's career center emails, the email doesn't follow the standard practices for opting out, double opt-in, nor does it even have those options in the email's footer or any identifying marks about why the user is receiving the email. A user could have registered with T-Mobile's old career center before the MetroPCS merger; but all that language is absent from the email:

|

| 2014-03-20, T-Mobile Careers Email Screenshot |

This email has only one call to action: Create a new profile. Hopefully this is just a one-time broadcast. Like with most things in life, you rarely have the opportunity to make a second impression.

LinkedIn: Gone Phishin'

One of the problems with automated platform emails is never knowing what you're going to get on the receiving end. Sure, there are plenty of people on my contact roster whose first name is "John" and others with the last name of "Smith", but the "John Smith" character simply does not exist. Maybe someone at LinkedIn thought it was clever way to add connections this way. What makes it weirder is the language of the email which reads:

"Your contact, John Smith, just joined LinkedIn

Help welcome John and get connected"

If he's already a contact, presumably farmed from the LinkedIn ecosystem, wouldn't he by default be in my network already? It makes me think this is a phising email since I don't know any John Smiths. And none exist in my LinkedIn connections nor among the apps that share contact data with LinkedIn.

"Your contact, John Smith, just joined LinkedIn

Help welcome John and get connected"

|

| 2014-03-12, mobile screenshot of LinkedIn notifications email |

If he's already a contact, presumably farmed from the LinkedIn ecosystem, wouldn't he by default be in my network already? It makes me think this is a phising email since I don't know any John Smiths. And none exist in my LinkedIn connections nor among the apps that share contact data with LinkedIn.

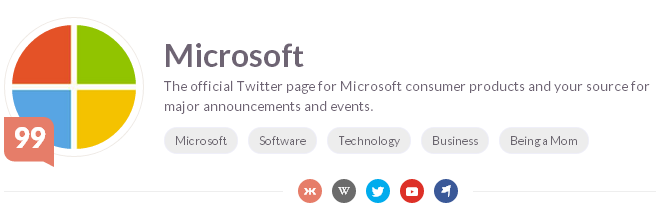

Klout and Unnatural Ranking

Klout started a while ago as a reputation ranking tool for users (and corporations) of social media. I only have one social property tied to Klout and as such, my Klout score is pitifully anemic (holding steady at 41, for just signing up and doing nothing much at all). I started looking at the scores of public figures and companies and then it dawned onto me that these entities have teams and a multitude of people contributing to and managing this score. Which really seems vastly unfair to those of us who represent small businesses. Sure, there might be a tinge of anger in this post; but I assure you it's for good reason.

Klout does nothing for my business. It doesn't help me generate leads or create new business opportunities; nor does it do anything for my clients who share the same online space on social media platforms. Klout doesn't even help a business gauge how well they are liked by customers who have purchased products or used their services. It's a useless "reputation" score that's generated by how frequent you post to your social network across multiple social networks. Seriously, neither I nor my followers and readers need that level of spam in our lives.

What bothers me is the inconsistency of how scores are calculated. It begs the question of today's random sceenshot:

How many tags does it take to get the phrase "Being a Mom" associated with Microsoft's Klout score? That's what I want to know.

Klout does nothing for my business. It doesn't help me generate leads or create new business opportunities; nor does it do anything for my clients who share the same online space on social media platforms. Klout doesn't even help a business gauge how well they are liked by customers who have purchased products or used their services. It's a useless "reputation" score that's generated by how frequent you post to your social network across multiple social networks. Seriously, neither I nor my followers and readers need that level of spam in our lives.

What bothers me is the inconsistency of how scores are calculated. It begs the question of today's random sceenshot:

How many tags does it take to get the phrase "Being a Mom" associated with Microsoft's Klout score? That's what I want to know.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)